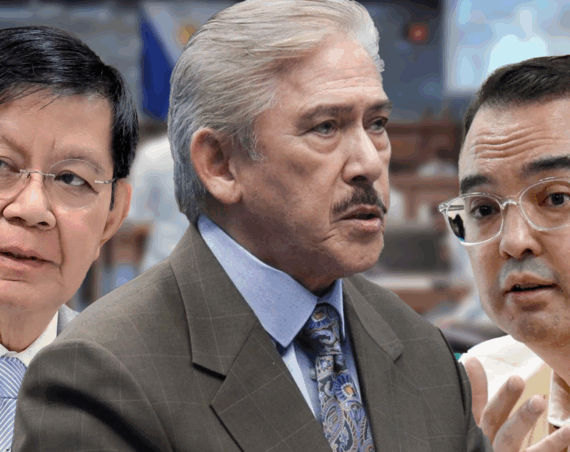

The ₱879,000-per-unit body-worn camera procurement of the Philippine Ports Authority (PPA) has drawn public outrage, after Senator Raffy Tulfo flagged it “immoral” and “scandalous.”

His demand was blunt: fire the members of the Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) and the Technical Working Group (TWG) that approved the deal with Boston Home Inc., a company with only ₱10 million in paid-up capital and an office reportedly located in a residential apartment.

But Tulfo’s call to remove only the BAC barely scratches the surface of accountability in the procurement of these body worn cameras.

Under Republic Act No. 9184, or the Government Procurement Reform Act, the BAC evaluates bids and ensures compliance.

Yet no procurement of this scale could have proceeded without the approval of the Head of the Procuring Entity (HOPE). In this case, Jay Daniel Santiago, who was PPA General Manager at the time and remains in the post today.

Just as importantly, such a transaction should not have proceeded without the oversight of the PPA Board of Directors and the Department of Transportation (DOTr).

The PPA Board, chaired by the DOTr Secretary, wields the agency’s corporate powers and signs off on major financial and policy decisions, including capital outlays such as the ₱340-million two-phase body camera system.

In 2020, Santiago was the head of procuring entity, while Arthur Tugade, then DOTr Secretary, sat as PPA Board chairman.

Santiago, in fact, approved the BAC resolution awarding the contract to Boston Home Inc. for the ₱879,000-per-unit purchase.

The Revised PPA Manual of Corporate Governance, adopted in December 2015, makes the Board’s duties even clearer.

It requires directors to “monitor and evaluate on a regular basis the implementation of corporate strategies and policies, business plans and operating budgets, as well as management’s overall performance to ensure optimum results,” and to “monitor and manage potential conflicts of interest of directors, management and officers, including misuse of corporate assets and abuse in related party transactions.”

Even if Tugade did not personally sign the BAC resolution, the Board he chaired had a continuing fiduciary obligation to watch over such transactions, spot red flags, and prevent misuse of public funds.

Santiago’s defense before the Senate, that the procurement was “transparent, competitive, and compliant” with the procurement law, was itself a quiet admission that he approved it.

His explanation that the nearly ₱1-million price per unit covered servers, connectivity, and system integration shows that top management, not merely the BAC, was fully aware of the pricing and scope.

Accountability, therefore, cannot be confined to mid-level staff who were simply implementing directives from above.

Even if the cameras were part of an integrated surveillance system, the huge disparity between the PPA’s ₱879,000 per unit and the Philippine National Police’s ₱135,000 per unit cannot be dismissed as a difference in specifications.

Tulfo’s proposal to “fire the BAC” risks turning the issue into an exercise in scapegoating.

The BAC’s role is recommendatory; its members, mostly mid-level officials, act under the authority of the General Manager and within the policy framework set by the Board.

If irregularities occurred, they were not just administrative errors but systemic lapses in leadership and governance—failures that the PPA Board and its chairman were duty-bound to prevent.

This procurement took place during the height of the PPA’s “port modernization” and digitalization push under Tugade and Santiago—a period marked by a string of expensive technology and surveillance projects that moved forward with little public scrutiny.

In the end, the buck stops at the top.

Senator Tulfo is right that the ₱879,000-per-camera deal is scandalous, but true accountability must go beyond the implementing committee.

Firing the BAC addresses the symptom, not the system that allowed the excess to happen.

EDITORIAL: The abuse of class suspensions has gone too far